Okinawa

Karate began as a common fighting system known as

te (Okinawan: ti) among the

Pechin class of the

Ryukyuans. After trade relationships were established with the

Ming dynasty of China by King

Satto of

Chūzan in 1372, some forms of

Chinese martial arts were introduced to the

Ryukyu Islands by the visitors from China, particularly

Fujian Province. A large group of Chinese families moved to Okinawa around 1392 for the purpose of cultural exchange, where they established the community of

Kumemura and shared their knowledge of a wide variety of Chinese arts and sciences, including the Chinese martial arts. The political centralization of Okinawa by King

Shō Hashi in 1429 and the policy of banning weapons, enforced in Okinawa after the

invasion of the

Shimazu clan in 1609, are also factors that furthered the development of unarmed combat techniques in Okinawa.

There were few formal styles of

te, but rather many practitioners with their own methods. One surviving example is the

Motobu-ryū school passed down from the Motobu family by Seikichi Uehara. Early styles of karate are often generalized as

Shuri-te,

Naha-te, and

Tomari-te, named after the three cities from which they emerged. Each area and its teachers had particular kata, techniques, and principles that distinguished their local version of

te from the others.

Members of the Okinawan upper classes were sent to China regularly to study various political and practical disciplines. The incorporation of empty-handed

Chinese Kung Fu into Okinawan martial arts occurred partly because of these exchanges and partly because of growing legal restrictions on the use of weaponry. Traditional karate

kata bear a strong resemblance to the forms found in Fujian martial arts such as

Fujian White Crane,

Five Ancestors, and Gangrou-quan (

Hard Soft Fist; pronounced "Gōjūken" in Japanese). Many Okinawan weapons such as the

sai,

tonfa, and

nunchaku may have originated in and around

Southeast Asia.

Sakukawa Kanga (1782–1838) had studied

pugilism and

staff (

bo) fighting in China (according to one legend, under the guidance of Kosokun, originator of

kusanku kata). In 1806 he started teaching a fighting art in the city of

Shuri that he called "Tudi Sakukawa," which meant "Sakukawa of China Hand." This was the first known recorded reference to the art of "Tudi," written as 唐手. Around the 1820s Sakukawa's most significant student

Matsumura Sōkon (1809–1899) taught a synthesis of

te (Shuri-te and Tomari-te) and

Shaolin (Chinese 少林) styles. Matsumura's style would later become the

Shōrin-ryū style.

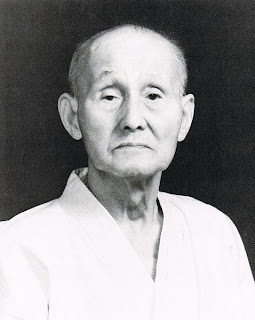

Ankō Itosu

Grandfather of Modern Karate

Matsumura taught his art to

Itosu Ankō (1831–1915) among others. Itosu adapted two forms he had learned from Matsumara. These are

kusanku and

chiang nan. He created the

ping'an forms ("

heian" or "

pinan" in Japanese) which are simplified kata for beginning students. In 1901 Itosu helped to get karate introduced into Okinawa's public schools. These forms were taught to children at the elementary school level. Itosu's influence in karate is broad. The forms he created are common across nearly all styles of karate. His students became some of the most well known karate masters, including

Gichin Funakoshi,

Kenwa Mabuni, and

Motobu Chōki. Itosu is sometimes referred to as "the Grandfather of Modern Karate.

In addition to the three early

te styles of karate a fourth Okinawan influence is that of

Kanbun Uechi (1877–1948). At the age of 20 he went to

Fuzhou in Fujian Province, China, to escape Japanese military conscription. While there he studied under Shushiwa. He was a leading figure of Chinese

Nanpa Shorin-ken style at that time. He later developed his own style of

Uechi-ryū karate based on the

Sanchin,

Seisan, and

Sanseiryu kata that he had studied in China.

Masters of karate in Tokyo (c. 1930s)

Kanken Toyama, Hironori Otsuka, Takeshi Shimoda, Gichin Funakoshi, Motobu Chōki, Kenwa Mabuni, Genwa Nakasone, and Shinken Taira (from left to right)

Gichin Funakoshi, founder of

Shotokan karate, is generally credited with having introduced and popularized karate on the main islands of Japan. In addition many Okinawans were actively teaching, and are thus also responsible for the development of karate on the main islands. Funakoshi was a student of both

Asato Ankō and

Itosu Ankō (who had worked to introduce karate to the Okinawa Prefectural School System in 1902). During this time period, prominent teachers who also influenced the spread of karate in Japan included

Kenwa Mabuni,

Chōjun Miyagi,

Motobu Chōki,

Kanken Tōyama, and

Kanbun Uechi. This was a turbulent period in the history of the region. It includes Japan's annexation of the Okinawan island group in 1872, the

First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), the

Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), the

annexation of Korea, and the rise of

Japanese militarism (1905–1945).

Japan was

invading China at the time, and Funakoshi knew that the art of

Tang/China hand would not be accepted; thus the change of the art's name to "way of the empty hand." The

dō suffix implies that

karatedō is a path to self-knowledge, not just a study of the technical aspects of fighting. Like most martial arts practiced in Japan, karate made its transition from -

jutsu to -

dō around the beginning of the 20th century. The "

dō" in "karate-dō" sets it apart from karate-

jutsu, as

aikido is distinguished from

aikijutsu,

judo from

jujutsu,

kendo from

kenjutsu and

iaido from

iaijutsu.

Gichin Funakoshi

Founder of Shotokan Karate

Funakoshi changed the names of many kata and the name of the art itself (at least on mainland Japan), doing so to get karate accepted by the Japanese

budō organization

Dai Nippon Butoku Kai. Funakoshi also gave Japanese names to many of the kata. The five

pinan forms became known as

heian, the three

naihanchi forms became known as

tekki,

seisan as

hangetsu,

Chintō as

gankaku,

wanshu as

empi, and so on. These were mostly political changes, rather than changes to the content of the forms, although Funakoshi did introduce some such changes. Funakoshi had trained in two of the popular branches of Okinawan karate of the time, Shorin-ryū and Shōrei-ryū. In Japan he was influenced by kendo, incorporating some ideas about distancing and timing into his style. He always referred to what he taught as simply karate, but in 1936 he built a dojo in Tokyo and the style he left behind is usually called

Shotokan after this dojo.

The modernization and systemization of karate in Japan also included the adoption of the white uniform that consisted of the

kimono and the

dogi or

keikogi—mostly called just

karategi—and colored belt ranks. Both of these innovations were originated and popularized by

Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo and one of the men Funakoshi consulted in his efforts to modernize karate.

A new form of karate called

Kyokushin was formally founded in 1957 by

Masutatsu Oyama (who was born a Korean, Choi Yeong-Eui 최영의). Kyokushin is largely a synthesis of Shotokan and Gōjū-ryū. It teaches a curriculum that emphasizes

aliveness, physical toughness, and

full contactsparring. Because of its emphasis on physical, full-force

sparring, Kyokushin is now often called "

full contact karate", or "

Knockdown karate" (after the name for its competition rules). Many other karate organizations and styles are descended from the Kyokushin curriculum.

The World Union of Karate-do Federations (WUKF) recognizes these styles of karate in its kata list.

Many schools would be affiliated with, or heavily influenced by, one or more of these styles.